Research & Treatment

Research & Treatment

The Center for Change eating disorder treatment program is based on cutting-edge research into eating disorders. The Center also conducts and publishes its own research on eating disorders, including on-going treatment outcome research. As new innovations in treating disorders are proven effective, they are incorporated into the Center for Change treatment program to enhance its effectiveness.

In keeping with current research findings and clinical guidelines, and in order to provide the best possible services in the most cost-effective manner, Center for Change offers a multi-dimensional, multi-disciplinary, stepped-care treatment program. Each client who comes to the Center for treatment participates in an ongoing comprehensive assessment which begins with an evaluation of their physical status, eating disorder history, associated psychiatric disturbances, substance use patterns, developmental history, family history and a thorough family interview. Based on this assessment, one or more levels of care will be recommended, depending on the severity of the client’s symptoms and specific eating disorder.

Our Treatment Focus

The Center’s primary focus is the treatment of individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Related characteristics treated include malnourishment, poor self-esteem, feelings of helplessness, family conflicts and traumatic life events such as abuse and sexual trauma. Other co-existing disorders such as depression, substance abuse, anxiety and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are also treated.

Recent research shows that approximately 75% of people diagnosed with eating disorders are females. Many of the women treated have conditions that have progressed to the point where they are unable to function independently or effectively in their family, work, school or social settings.

Our Research Department’s Mission

The mission of Center for Change research department is to conduct research and collect data that will (1) document the effectiveness of the Center’s treatment programs, (2) help increase the effectiveness of the Center’s treatment programs, (3) give the Center recognition in the eating disorders treatment field, and (4) contribute to new discoveries and better understanding about how to effectively treat eating disorders.

Research Values

The personnel in Center for Change research department believe that it is essential for professionals who treat patients with eating disorders to monitor the effectiveness and outcomes of their interventions with carefully conducted research. We believe that research is essential for documenting and improving the effectiveness of eating disorder treatment programs, and for increasing helping professionals’ understanding of these disorders. We believe that as the findings of our research, and the research of others, is made available to the treatment staff at Center for Change, the effectiveness of the Center’s treatment programs will continue to increase. We also believe that our research may contribute to other helping professionals’ ability to more effectively treat patients with eating disorders.

Research Department Staff

The Research Department at Center for Change is staffed part-time by several personnel:

Peter Sanders, PhD, Research Director

Nicole Hawkins, PhD, CEO, Center for Change

A Guide for Loved Ones, Patients, and Providers

Center for Change is pleased to share the REDC Guidebook, created by the Residential Eating Disorders Consortium (REDC) in partnership with the National Alliance for Eating Disorders.

This resource helps individuals, families, and professionals navigate today’s evolving treatment landscape - where in-person, virtual, and hybrid options are available. It offers practical guidance on evaluating levels of care, understanding ethical standards, identifying red flags, and finding the right clinical fit for each person’s needs.

Patient Satisfaction Scores

Published Articles

Center for Change Outcome Research Program

Since Center for Change opened its doors in 1996, we have conducted outcome research to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of our treatment program. We have published reports of our research in professional journals and books (e.g., Richards, Hardman, & Berrett, 2007). We use a variety of measures to assess patients’ progress. We assess specific eating disorder symptomatic behaviors such as bingeing, purging, and food restriction as well as beliefs about food, dieting, body shape, and so on. We also assess patients’ general psychological and spiritual functioning by using measures of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, interpersonal relations, social role functioning, loneliness, and spiritual well-being. All patients are assessed on the above dimensions when they are admitted to our inpatient and residential treatment programs and, if possible, when they are discharged from the program. We also conduct periodic follow-up surveys with former patients from 3 months to 10 years after they complete treatment to assess their long-term progress and recovery rates. Below is a brief summary of the major findings of our treatment outcome research:

Read about the findings here (2021-2023)

Read about the findings here (2019)

Understanding Eating Disorder Treatment Outcome Claims

Because there is no consistency in how recovery and improvement rates are calculated from treatment center to treatment center in North America, it is difficult to make precise comparisons between them concerning their effectiveness. In addition, some treatment centers make exaggerated claims about the percentage of their patients who recover during treatment (e.g., one well-known treatment center published claims on its website that approximately 98% of patients achieve recovery). Reputable scientific studies cast serious doubt on such claims.

In a comprehensive review of the long-term outcome studies of treatment for anorexia nervosa published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Steinhausen (2002) concluded that less than 50% of patients with AN recover, 33% improve, and 20% remained chronically ill. In comprehensive review of the treatment outcome studies of bulimia nervosa, also published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Steinhausen & Weber (2009) concluded that approximately 45% of patients with bulimia nervosa recover, 27% improve considerably, and nearly 23% have a chronic protracted course (didn’t improve). Several other reviewers have arrived at similar recovery estimate percentages for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (e.g., Richards, Baldwin, Frost, Clark Sly, Berrett, & Hardman, 2000; Steinhausen, 1995; Yager, 1989).

As you look for an eating disorder treatment center for your loved one be cautious if you encounter claims that virtually all patients recover or are cured by a treatment program. It is unlikely that such claims are accurate. They are undoubtedly not based on reputable scientific evidence.

Center for Change Outcome Research Program

Since Center for Change opened its doors in 1996, we have conducted outcome research to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of our treatment program. We have published reports of our research in professional journals and books (e.g., Richards, Hardman, & Berrett, 2007). We use a variety of measures to assess patients’ progress. We assess specific eating disorder symptomatic behaviors such as bingeing, purging, and food restriction as well as beliefs about food, dieting, body shape, and so on. We also assess patients’ general psychological and spiritual functioning by using measures of depression, anxiety, interpersonal relations, social role functioning, loneliness, and spiritual well-being. All patients are assessed on the above dimensions when they are admitted to our inpatient treatment program and, if possible, when they are discharged from the program. Below is a brief summary of the major findings of our treatment outcome research.

Outcomes at Completion of Inpatient Treatment

Two scientifically validated measures of attitudes and beliefs about eating, dieting, and body shape, are administered when patients are admitted and discharge from CFC: the Eating Attitudes Scale and Body Shape Questionnaire. Additionally, measures of general psychological distress, depression symptoms, and social role functioning were administered. Data from CFC’s 15 year treatment outcome study have repeatedly confirmed that patients show clinically significant improvement on both of these measures suggesting that, on the average, patients acquire much healthier attitudes and beliefs about food, dieting, and body shape during their inpatient stay at the CFC. Additionally, CFC conducts ongoing assessment of each of these areas with all patients who attend inpatient and residential treatment services. The results below are from data collected from January 1, 2021 to October 28, 2025.

Eating Attitudes

Figure 1 shows how scores on the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) decreased following treatment at CFC. The red horizontal line represents a cutoff score for whether a person is considered at risk of having an eating disorder. Although the score is still above this threshold, it is much closer to what would be expected for outpatient compared to inpatient treatment. Thus, on average, when they complete inpatient treatment, Center for Change patients’ concerns about food, dieting, and weight are much less intense and are much closer to a non-clinical range. The change was statistically significant with an effect size of d=1.14 suggesting a large effect.

Figure 1. Reductions in Eating Disorder Symptoms as measured by the Eating Attitudes Test (e.g., anxiety about eating, preoccupation with food, vomiting, dieting, and weighing oneself frequently.

Body Shape

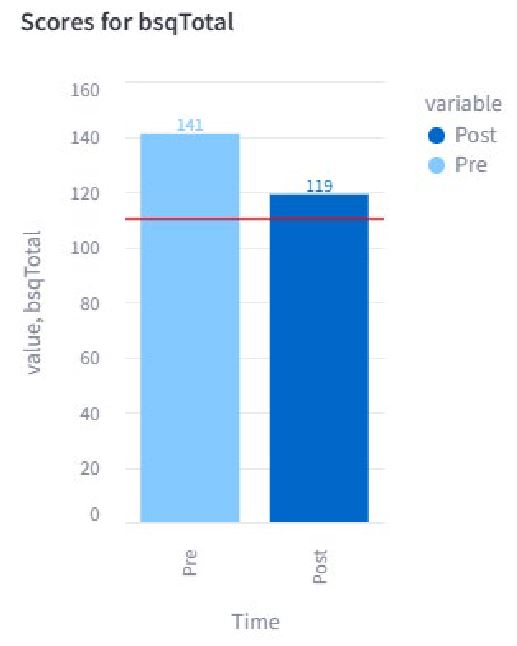

Figure 2 shows that when CFC patients complete inpatient treatment, their concerns about their body shape and size are much less intense and are very close to the non-clinical range for women (women without eating disorders score 110 and below on the BSQ). The difference was statistically significant (p < .01) with a medium size (d=.57) Although it does not quite meet the threshold for non-clinical levels of distress, it does suggest a that patients are closer to an outpatient level of eating concerns, which would make a step-down in care appropriate.

Figure 2. Reductions in Unhealthy Perceptions of Body Image and Shape as measured by the Body Shape Questionnaire (e.g. feeling too fat, wanting to be thinner, feeling ashamed of one’s body).

General Psychological Distress

The patients’ level of psychological, relationship, and social role distress as measured by the standardized and widely used Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45) also significantly decreased. In Figure 3 it can be seen that after participating in the CFC inpatient program, on average, patients’ psychological distress (anxiety and depression symptoms), interpersonal relationship distress, and social role conflict were all much less intense. Although these scores are still in the clinical range, their levels of general psychological distress improved significantly (with an effect size of d=.49) and are indicative of reliable change (14-point decrease is the reliable change threshold). Similar to other measures, this suggests a need for ongoing care, but at a much less intensive level.

Figure 3. General Psychological Distress as measured by the Outcome Questionnaire 45 (OQ-45).

Depression

The patient’s levels of depression were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Figure 4 shows the results from the PHQ-9. These results suggest that clients experience a decrease in depressive symptoms going from moderately severe symptoms (15 and above) to the low end of moderate symptoms (10 and above). These changes also nearly meet the criteria for a clinically significant change (5 point decrease). Additionally, the changes were statistically significant (p < .01) and had a medium effect size (d= .54). Thus, although CFC is primarily an eating disorder treatment facility, there still appears to be a decrease in depressive symptoms, but less so than on measures of eating disorders.

Figure 4: Depression scores as measured by the PHQ-9.

Discussion

The improvements in CFC patients’ psychological well-being reported here are based on approximately 703 patients from January 1, 2021 to October 28th , 2025. These data collectively provide strong evidence that on average, Center for Change patients get significantly better during their inpatient stay at the CFC in various domains. On average, patients made large improvements in their attitudes toward eating and in their perception of their body image. Changes were not as large in other areas, but still represented clinically meaningful decreases. These data provide evidence that the CFC inpatient program successfully helps the average patient make a “jump start” toward a healthier life by helping them make important and healthy changes in their symptoms, beliefs, and behaviors in a short period of time.

Conclusion

The vast majority of Center for Change patients achieve large improvements during their inpatient stay at the CFC. At the conclusion of treatment, the average CFC patient demonstrated significant improvements by the end of treatment in several areas of psychological functioning. These eating disorder treatment outcomes are equivalent and often superior to other responsible, scientifically valid reports of patient improvement that have been reported in the research literature. Center for Change is a place of hope and healing. Scientific treatment outcome research has documented this is true.

References

Richards, P. S., Baldwin, B., Frost, H., Clark-Sly, J., Berrett, M. E., & Hardman, R. K. (2000). What works for treating eating disorders? Conclusions of 28 outcome reviews. Eating Disorders: Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 8, 189-206.

Steinhausen, H. (2002). The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1284-1293.

Steinhausen, H. & Weber, S. (2009). The outcome of bulimia nervosa: Findings from one-quarter century of research. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 1331-1341.

Steinhausen, H. (1995). The course and outcome of anorexia nervosa. In K. D. Brownell & C. G. Fairburn (Eds.). Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 234-237). New York: The Guilford Press.

Yager, J. (1989). Psychological treatment for eating disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 19 (9), 477-482.

Summary of Research Department Accomplishments

During the past 20 years, the Research Department at Center for Change has published 3 books, 5 book chapters, and 16 professional journal articles. Members of the Research Department and their collaborators have also presented research at numerous professional conferences. Center for Change has also sponsored 10 doctoral dissertations. The Research Department also provides regular treatment outcome reports to Center for Change administration and treatment staff to assist in performance improvement. A listing of publications and other scholarly contributions by members of the Research Department and their collaborators can be found here.

Recently Completed Research Projects

Investigation of intuitive eating with patients in an eating disorder inpatient treatment program: A two-year prospective study. Smith, M., Passmore, K., Richards P. S., Hawks, S., & Madanat, H. Presented at the International Conference on Eating Disorders (ICED) of the Academy for Eating Disorders (AED) on May 2, 2013 in Montreal, Canada.

Center for Change collaborated with research at several universities in the United States on a study concerning the helpfulness of teaching patients how to eat intuitively during their stay in the treatment program.

Summary of Study

Intuitive eating is characterized by eating based on physiological hunger and satiety cues rather than situational and emotional cues. Several psychologists, nutritionists, and health science professionals have argued that this style of eating is adaptive and research studies have shown that it is associated with positive self-esteem, body image, and weight maintenance and/or loss, as well as reduced cardiovascular risk and greater pleasure and less anxiety associated with eating. Nevertheless, there is limited evidence concerning the effectiveness of intuitive eating with eating disorder patients. Controversy exists in the eating disorders field concerning the question of whether it is possible for patients with eating disorders to learn how to eat intuitively, and whether attempting to teach this skill is helpful or harmful. We conducted a two-year prospective study where we evaluated whether teaching intuitive eating to patients in an eating disorder inpatient treatment program was effective.

Measures

•Intuitive Eating Scale (IES; Hawkes, Madanat, & Merrill, 2004), 30-item

•Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979), 40-item

•Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) (Cooper, Taylor, Cooper, and Fairburn, 1987), 34-item

•Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2) (Lambert, Okiishi, Finch & Johnson, 1998)

•Theistic Spiritual Outcome Survey (TSOS; Richards, Smith), 17-item

Major Findings and Conclusions

•Significant improvements in eating disorder patients’ ability to engage in intuitive eating behaviors and attitudes.

•The analysis of the IES scores showed that the eating disorder patients’ scores significantly increased between the time they were admitted to the Inpatient treatment program and transitioned into the Residential treatment program. Their scores also significantly increased between the time that they began the Residential treatment program and at the time they were discharged from treatment.

•As a group, the patients’ increases in their ability to eat intuitively were large and clinically significant (the effect sizes were large and ranged from .68 to 1.44). The clinicians perceived that the patients’ attitudes about food grew healthier during treatment (the effect size was large—.89).

•Dieticians also perceived that the patients’ ability to eat intuitively improved during treatment, and that their attitudes toward food and eating became healthier during the course of treatment, although their estimates of patients’ progress on these issues were more reserved (effect sizes ranged from .29 to .58).

•Patients’ scores on the EAT, BSQ, OQ45.2, and TSOS all improved significantly between the time of admission and the time of discharge from the treatment program. These changes were large and clinically significant (three of the effect sizes were large and ranged from 1.02 to 1.91; the TSOS effect size was the only small one at .36).

•Patients’ scores on all of these measures at the time of discharge fell into normal ranges, or close to it.

•At the time patients were discharged from the treatment program, the Hawkes Intuitive Eating Scale (HIES) correlated significantly with other indicators of positive treatment outcomes, including reduced eating disorder symptoms (as measured by the EAT),

improvements in patients’ perceptions of their body size and shape (as measured by the

BSQ), reductions in psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, relationship conflict, and social role conflict (as measured by the OQ-45.2), and improvements in what patients felt about their spirituality and moral congruence (as measured by the TSOS).

•In summary, the findings of our 2-year prospective study provide strong evidence that intuitive eating behavior and attitudes can be taught and learned in an inpatient and residential eating disorder treatment program, and that improvements in patients’ ability to eat intuitively are associated with other important indicators of healing and recovery. That intuitive eating principles can be effectively integrated in a highly structured treatment in light of the many medical, nutritional, and psychological considerations, provides sound evidence for their incorporation in inpatient and residential eating disorder treatment.

There is a need to investigate whether intuitive eating skills and attitudes can be learned as effectively for different types of eating disorder patients. For example, do patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder differ in their ability to acquire intuitive eating skills, attitudes, and behaviors? Are there differences between adolescent and adult patients in their ability to acquire intuitive eating skills, attitudes, and behaviors?

Effects of providing patient progress feedback and clinical tools to psychotherapists in an inpatient eating disorders treatment program: A randomized controlled study. (Simon, W., Lambert, M. J., Busath, G., Vazquez, A., Berkeljon, A., Hyer, K., Granley, M., & Berrett, M. (2013). Psychotherapy Research, 23 (3), 287-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.787497

Center for Change recently collaborated with researchers from the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, in Warsaw, Poland, and Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah, to investigate the effects of giving feedback to therapists about their patients’ progress on the levels of patient improvement at the conclusion of treatment. Listed below is the reference and abstract for this recently published research study.

Abstract

Research on the effects of progress feedback and clinician problem-solving tools on patient outcome has been limited to a few clinical problems and settings (Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, 2010). Although these interventions work well in outpatient settings their effects so far have not been investigated with eating-disordered patients or in inpatient care. In this study, the effect of providing feedback interventions was investigated in a randomized clinical trial involving 133 females diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or eating disorders not otherwise specified. Comparisons were made between the outcomes of patients randomly assigned to either treatment-as-usual (TAU) or an experimental condition (Fb) within therapists (the same therapists provided both treatments). Patients in the Fb condition more frequently experienced clinically significant change than those who had TAU (52.95% vs. 28.6%). Similar trends were noted within diagnostic groups. In terms of pre to post change in mental health functioning, large effect sizes favored Fb over TAU. Patients' BMI improved substantially in both TAU and the feedback condition. The effects of feedback were consistent with past research on these approaches although the effect size was smaller in this study. Suggestions for further research are delineated.